You can listen to the Cathouse cassette only album Virtue Undone here -- for entertainment and educational purposes only, a lofi rip from my personal collection:

https://soundcloud.com/teacherontheradio/sets/cathouse-virtue-undone

The Other End - arts and entertainment supplement to the South End

the Wayne State University student newspaper

Detroit, Michigan

1992

by Andrew/Sunfrog, writing as “Ellen Carryout”

Finney’s Pub, Detroit, July 1992

Eric Walworth is creating a feedback warzone with his guitar. As I bask in this aural onslaught, I ponder the possibilities down tall glasses of beer. I watch the glassy audience's eyes animate with the knowledge of dreams.

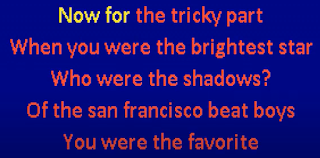

And Elizabeth sings: “If you look inside your dreams you will find me.”

She breathes big ideas in this tiny room. The band builds bridges of sound, past pitchers of beer and into pictures of reverie and hope.

This Corridor band is, of course, Cathouse. They’ve been receiving an abundance of praise in the press in recent days, and this cozy pub is overflowing with old friends and curious seekers. What they’ve created is actually quite simple, yet profound. Cathouse is a passionate rock-n-roll band for the people of this neighborhood.

Just when I thought the tired flesh of rock music had been trivialized and parodied beyond repair, a band like this comes along to inject a new boogie into my aching bones. I never thought something as old-fashioned as four-piece could translate rock-n-roll into a transcendent noise to transform my soul.

“Don’t believe all that shit about rock-n-roll being dead,” says Elizabeth. “That’s propaganda designed to separate you from things that help you feel alive.”

She has become a sort of spokeswoman for forgotten ideals and the darker side of her own heart, which she wears out in her vocal verisimilitude with embarrassing honesty. With an innocent flare, she lets her music flow as any artsy-extrovert should, declaring, “I’m serving the community. I’m serving the people who see the band. I’m serving the music that comes through me.”

In Every Direction, Without A Drummer, Detroit 1989

In October 1989, Cathouse played their first gig as an uncertain 3-piece at the Paradigm Center for the Arts, a dance studio/loft in Harmonie Park. The show was a Community Concert Series benefit for the Womyn’s Own Collective and a bashfully brave beginning without a backbeat. Elizabeth had that loud, clear voice. Eric and bassist Jim Johnson made a lot of noise.

It would be many moons and a thousand mood swings before Cathouse would get into the tight-knit, groove-giving, post-garage geniuses that they are today. Finding drummer Tim Suliman was the turning point to take them beyond the modest aspirations of only playing clubs on the Corridor circuit.

A growing hunger and insatiable ambition have taken them on many midwest mini-tours, and it now seems only a matter of time until some van gets packed full of gear to take them places they’ve never seen before.

A House on Commonwealth Street

Cathouse began in a townhouse with nine cats and high ceilings. Elizabeth and Eric lived there alone with the feline scent and the Fender Strat. Elizabeth used to listen to Eric practice. She’d be upstairs. He’d be downstairs. The music would bring them together.

“He was young in it, and I’d encourage him,” Elizabeth recalled. “I’d see him doing this wild-man, sensual, crazy thing, pulling the shit out of his strings and throwing his guitar around. I’d say, “Oh my god! That’s hot. You gotta do that onstage in our band.’ He’d get all shy and everything. I can’t think of Cathouse without Eric. i just can’t. We’re very different, and the friction between us makes it mean something, that we stay together as an example of cooperation.”

As Cathouse became a band, each member became more of a musician, and they grew together. The critical response back in those early days was rather dismal. What is now a devoted following was then just a scattering of sympathetic friends.

Elizabeth expands: “I was singing simple straight songs in a simple straight voice. As time progressed, I became more mature and free with my gift. I’ve been able to understand singing as a place where I can be tortured, be angry, be growling, be violent, be lust and be afraid. It’s been an evolution for me to understand all the places I can go with my voice and all the sensations that can emanate from my body onto an audience through my voice. My vocabulary has grown.”

Fierce, Bold and Resourceful

Much noise has been made about the gritty, grunge guitar roots of Detroit rock-n-roll as made manifest by the MC5 and the Stooges. I’ve heard critics wave that obvious flag a thousand times it seems. Elizabeth has pulled down some reason for this mythos and put it in its proper contemporary context:

“This band wouldn’t be what it is without this neighborhood. I don’t know if I can even comprehend us existing without Detroit, because we’re so much in this place. We’ve had the good fortune to learn how to perform in front of audiences that have been accepting, loving, and curious. This neighborhood, from Woodward to Trumbull, from Mack to Antoinette, is where Cathouse comes from. We are poor, fierce, and resourceful. And incestuous sometimes. The desire to commune gives us strength. Our ancestors had it. Now that communing is less possible, for people to join and unite seems like a miracle to me. But it’s an old impulse, an organic impulse.”

So Detroit gives bands a “heat-hunger-bare bones-no bullshit-intensity” that Elizabeth has noticed in other groups such as Mick Vranich and Wordban’d. This energy is most palatable when bands leave Detroit to gig in other places. You can feel the difference.

From singing to painting and back again

As an actress, songstress, painter, and poet, Elizabeth is clearly a multi-dimensional artist. The canvas and the song seem to inspire her the most as they come from one body.

“I have a personal vision almost all the time. Singing is the place I give voice to those pictures in words. Painting is where I give voice to those pictures in paint. Painting helps me be quiet, it helps me be still. Being in the band is a more social experiential thing. I’m in a sea of people and a sea of noise.”

As Elizabeth sings about big ideas in her shameless uninhibited manner, she runs the risk of having her sincerity overshadowed by its own grandiosity, no matter how genuine it may be. How does she feel about that challenge?

“I feel uncomfortable speaking in a language that doesn’t feel appropriate to me. That makes me feel icky. I don’t want to project an image of myself onto the world, I just want to be myself in the world.”

In contrast to our collective urban backdrop of “abandonment, desolation, waste, and fear,” we have voice, which Rico Africa called the “siren of industrial noir,” crying out, shouting out, singing out loud:

“I’ve got this eerie feeling coming over me . . ."

Cathouse, “Don’t give it up.”